Drug Cartels Are Evolving: Military and Organisational Transformation of Mexican Cartels 1970 - 2025

From Ye Olde Family Mafias to Cocaine McDonalds with Private Armies

Throughout this article I employ the term ‘cartel’ liberally as a catch all to refer to all organised criminal groups in Mexico. This is how it is conventionally used both informally and in the media so for the sake of clarity it is the term I will use.

The Mexican cartels are often in the news these days, yet other than their acts of brutality and obscene earnings not much else is generally reported or discussed. Some writers and podcasters on the right talk about how the cartels are ‘taking over’, though little reason is given why and how. Almost all coverage is an attempt to push the reader into supporting military action against the cartels by the United States or alternatively, a loosening of US drug laws that will supposedly cripple the cartels. In my reading, I’ve been surprised by the little discussed transformation of these cartels over the last few decades from classic family-based mafia groups to dynamic self-replenishing cell structures that closely resemble the franchise system used by famous American companies such as McDonalds, Subway and Planet Fitness. There hasn’t only been innovation in organisational structure either, but also how they interact with the world around them. Para-military strategy and tactics have largely replaced tit-for-tat assassinations and video recorded beheadings replaced what would have previously only been silent killings. IEDs and now drones are also being used in direct confrontations against the Mexican military – something that would have been unfathomable in the 1980s to mid 2000s. Moreover, the cartels as a whole don’t seem to be losing.

The Beginnings

In 1929, the party that became known as the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) seized power, it reigned for 71 years all the way to the year 2000. The one-party state devolved into a naked, country-wide, corrupt patronage network. During the 1960s and 1970s familial groups formed that would grow marijuana and smuggle the produce across the border into the United States. These groups made a tidy profit, but what they were doing was of course illegal. Though, the aforementioned highly corrupt Mexican state would be willing to overlook their crimes for a fee and a promise that violence and drug sales to the Mexican populace would be minimised.

The arrangement worked well. Government gears were greased with weed money and the crime families earned a solid income. Importantly, in the 1970s Columbian cocaine traffickers began to move vast quantities of contraband over the Caribbean to the United States. But by the 1980s the US government was cracking down on the Caribbean route, closing the Columbians’ narco-islands and rendering the route non-viable. The change required the lucrative cocaine to be trafficked to the US overland through Mexico. This, coupled with an almost comically corrupt Mexican government made for the ideal incubator for early Mexican drug trafficking groups.

Intermediaries with the Columbian cartels, chiefly the Honduran Juan Matta-Bellesteros, collaborated with influential and well networked figures within Mexico’s nascent drug world such as Miguel Felix Gallardo to organise profit sharing agreements for Columbian-made cocaine smuggled into the US. The arrangements could be quite simple; Columbian cartels would handle the growing and processing, making cocaine available Mexican groups (the coca plant whose leaves are refined into cocaine do not grow well in Mexico, but do well in Columbia) to traffic to the US and the profit would be split.

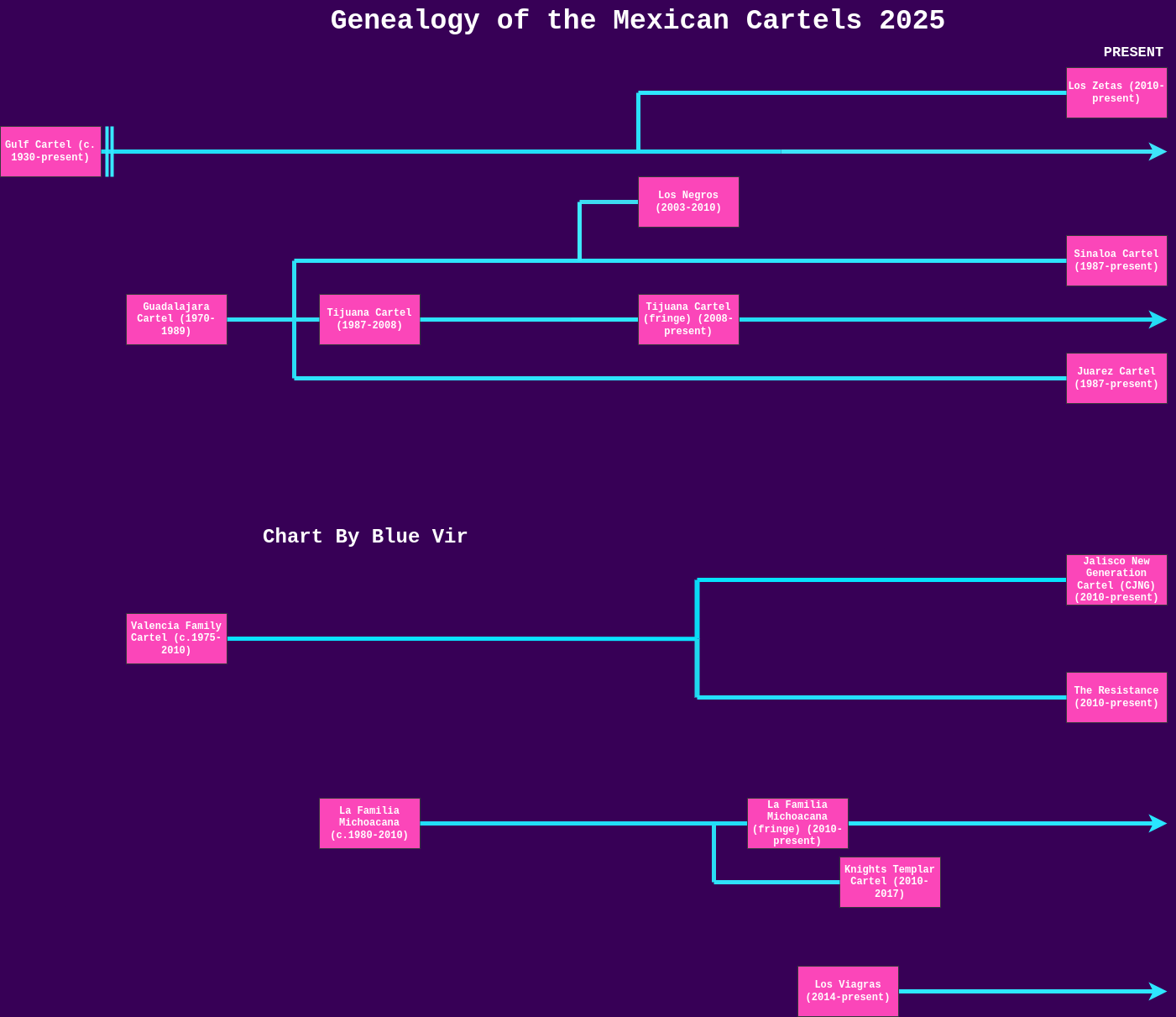

The level of overall centralisation of the ‘Guadalajara Cartel’ -- the group headed by Miguel Felix Gallardo ‘founded’ around 1978-- is often exaggerated. It can more accurately be described as a network of crime families coordinated by Gallardo. The mafia-style family system was rigid and the scope of violence was limited. The crime families existed underneath local governments and expressed little hard power beyond assassinating targets and street scuffles. Things reached a local high-point in 1985 when a group overseen by Gallardo were involved in what was an unprecedented 30 hour long torture and murder of American DEA agent Enrique Camarena. It was a brutal act. The agent had his bones broken and skull penetrated by a drill --perhaps while he was still alive-- without mentioning other gruesome details. This made the up until then widespread tacit cooperation between Mexican officials and the drug families intolerable to the United States government. Miguel Felix Gallardo became the public enemy and was arrested by Mexican police in 1989.

The Evolutionary Selection Pressure – Early Crackdowns and High-Value Targeting

Infiltrating any criminal organisation, never mind familial criminal organisations to arrange sudden mass-arrests of mid-levels required to kill an organisation is long and hard. It’s even harder in a corrupt state where confidential government information leaks like a sieve. Going after the rich and famous drug king-pins however gains much notoriety for the officials involved and is comparatively simpler to execute, and has an alluring rationalisation that one is ‘cutting the head off the snake’ and paralysing an org by taking out its leadership. It is therefore not so surprising that the Mexican strategy was less focused on wiping out the mid-level, but instead on taking out the leaders.

In 2006 when the new president Felipe Calderon declared a literal war on drugs and authorised military force against the cartels they used the term ‘High-Value Targeting’. It would be one of the main guiding philosophies that determined the military’s course of action. It was successful in a narrow way. Old patriarchs were killed and centralised familial groups broke apart. This selective pressure against centralised familial cartels would be the catalyst for a new kind of cartel, one that is dynamic and can effectively regenerate itself and replicate after leadership is taken out. Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generacion aka CJNG aka Jalisco New Generation Cartel is the most effective and fascinating product of this new era. CJNG was born from the ashes of the Valencia Family Cartel in 2009. It has an ingenious franchise-cell structure that weeds out ineffective upper mid-level leaders and allows more seamless incorporation of new groups into the cartel and confers greater integrity when faced with high-level arrests and assassinations. A spiffy description I give to CJNG is cocaine McDonald's with private armies.

How Does CJNG Work?

With McDonald’s, the franchisee raises his own capital to work within the McDonald’s franchisee guidelines which gives him access to the McDonald’s food products, supply chain, brand and marketing. A successful franchisee utilises the McDonald’s proprietary range of products to run a highly profitable restaurant with less risk and a gentler learning curve than if he started his own restaurant. A successful McDonald’s franchisee may own many McDonald’s franchises, taking on the risk himself and funded by his own success. The successful franchisee benefits McDonald’s Corporation as McDonald’s Corporation owns the real estate and makes money distributing licences and products to the franchisee. The franchise system means that McDonald’s Corporation doesn’t rely on unaccountable salaried bureaucrats and managers to generate profits or have financial exposure to their mistakes. In this elegant system, a poorly run or unlucky restaurant simply looses money for the franchisee with little downside to McDonald’s Corporation, as McDonald’s Corporation didn’t invest their own capital.

In CJNG there are the elite central forces, headed by the leader Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes aka El Mencho (arrested in Nov 2024). The central forces are comparatively highly disciplined and often recruited from Mexican army and special forces deserters. El Mencho and the central leadership has specialists and connections with Chinese and Colombians that give them access to drug products (chiefly fentanyl precursors and cocaine) and has established drug routes to the United States that CJNG gang affiliates gain access to when they join under the CJNG banner. Much of the day-to-day fighting and trafficking is handled by the affiliate gangs who’ve joined under the CJNG banner. They function similarly to a restaurant or retail franchises.

Competent leaders of small gangs can approach CJNG, they may be given assignments, perhaps killing some rival cartel members or organising the transportation of drugs across a certain area in return a portion of the money which the small gang makes will be claimed by the central CJNG leadership. CJNG will provide the drugs or other goods, and the franchisee will handle the rest. If the franchisee is killed or arrested or becomes unpopular with his men who mutiny there is minimal exposure to CJNG. Infighting within a franchise is not necessarily a bad thing, for example an ambitious popular member of the gang killing an unpopular ineffective gang leader. All the better for CJNG if he manages the gang better as long as he still aligns with CJNG. In this case the new leader’s franchise will likely accrue more men over time, perhaps growing a gang of a dozen men into the hundreds, all earning more revenue and prestige for himself and the CJNG leadership.

If CJNG’s position is threatened by a rival cartel or a rival cartel is moving in on territory of the central leadership or a franchisee, or if the CJNG central leadership wants to make a serious push against a rival cartel then a coalition of franchisees and the elite central forces can be rallied. The coalitions of numerous franchise gangs and the elite central army have proven to extremely effective. It has allowed CJNG to become the primary or perhaps secondary player in the multi-hundred billion dollar Mexican organised crime sector within 15 years.

Changing Nature of Cartel Violence

In the before times, the scope of cartel violence was comparatively narrow. There were assassinations committed by sicarios larping as ranchers and the odd gun fight with the police and rival cartels. There were some kidnappings and quiet assassinations (other than the Camerena incident). The military were never engaged.

Then the 2000s came. Video recorded beheadings took the place of in many cases what would’ve been under-the-radar killings. Low pay and poor conditions in the military led to large numbers of desertions – it is estimated that at least 150000 Mexican soldiers deserted from the military between 2000 and 2016, especially from 2000 to 2006. Of these, it is estimated that 1/3 (that is, at least 50000) became involved with the cartels. This all happened around the aforementioned cartel crackdown where the familial cartels were broken. It was the perfect storm. New and nimble criminal groups integrated military tactics and skills, the cartel members’ rancher ideal was replaced with the special forces soldier ideal. Engagements got larger, more direct and more deadly. The military, now brought into the conflict due to Felipe Calderon’s new policy, began to face serious challenges handling this threat.

The change is best exemplified by the government’s failure to extradite the son of famed drug lord El Chapo, Ovidio Guzman Gomez in 2019. In 2019, the government initiated a plan to arrest and extradite Gomez to the United States. Gomez’s house was raided and he was detained, but a force of over 700 Sinaloa cartelmen began attacking military bases, police stations and other buildings. In the carnage of it a prison break was successful and 53 prisoners escaped. The cartelmen then threatened to massacre civilians in an area where military families resided and took 8 soldiers hostage. The cartelmen succeeded in their goal of bending the government into submission as Ovidio Guzman Lopez was released by the police. This is what the state losing its monopoly on violence looks like. Outright defiance and brute forcing the state to act a certain way is a major departure from the methods of the cartels of old. The old cartels would’ve made extensive use of bribery and blackmail, but never consider massacring civilians or at least credibly threatening to do so to achieve their goals. The threat in 2019 was credible because the cartels had overpowered local military and police forces.

The Iraq War showed the world how debilitating IEDs could be to even the most modern military forces. In Iraq, IEDs were responsible for the majority of deaths of American soldiers – not to mention the many more American servicemen who were maimed and permanently disabled. Due to the omnipresent threat of the IEDs, American troops were forced to spend an inordinate amount of time cooped up in heavily armoured troop transports, constraining operations. Since 2020, the use of IEDs by Mexican criminal groups has rapidly increased. According to InsightCrime, between 2020 and 2021 only three IEDs were seized, but this has blown up to 1375 in 2022, 1681 in 2023 and as of October 2024, 2024 reached 1571. This came after a deadly attack on authorities via IED detonation in 2022, where four police officers and two civilians were killed. This would be the first of many successful IED attacks. IED attacks cause disproportional damage compared to the initial investment and then take a disproportionate amount of resources to counter.

Compare the effort of building and placing an IED to the authorities’ counter-measure of scouring the roads then calling in bomb specialists to remove IEDs safely (if they are successful). Asymmetric war in a nutshell. This causes a massive drag on policing and military resources. If IEDs are utilised to their fullest extent, the mobility and response of Mexican authorities to these criminal groups will be severely constrained. IEDs have been given 3 new operational axis as they have been combined with First Person View (FPV) drones. Ukraine has been for FPVs what Iraq was for ground IEDs. FPV drones can move at speeds and with such agility that it is not practical for even highly trained marksmen to shoot them down with any reliability. Unlike IEDs placed on the ground, FPVs are dynamic and respond to the battlefield environment which allow them nullify a wider variety ground-based operations.

For example, ground-based IEDs require the attacker to anticipate the journey of the opponent, so IEDs will predictably be placed on roads, while FPVs can be used actively in any circumstance and require minimal opponent prediction. The main counter-measure to FPVs – signal jamming – also affects radios, which has disproportionately negative effects on the combat effectiveness of professionals utilising the signal jammers as they are trained for better group co-ordination compared to the more ragtag narcomen. This doesn’t account for the fact that signal jammers have also been effectively countered by fiber-optic connected drones, though I have not seen any evidence for their use in Mexico so far. None of this bodes well for the Mexican authorities.

Diversification

Mexican cartels have moved beyond just the production and distribution of drugs into other sectors, namely petroleum theft, illegal logging and many different types of extortion. At a certain point, approximately half of Los Zetas’ revenue came from non-drug sources. I am very sceptical of liberal activists who claim that if drugs were decriminalised in the USA that cartel profits would collapse and therefore the organised crime would mostly go away. The liberal activists appear to only use the cartels as a veneer to push their agenda of drug legalisation and decriminalisation (which could end terribly for the United States, but may be de facto inevitable, a future article perhaps). If drug prices in the United States crashed —either due to the dollar severely declining relative to the Mexican peso or due to drug decriminalisation—heavily armed criminal groups within Mexico will not disappear, perhaps the organisations will but the human capital won’t. Remnants from these organisations will find new niches, perhaps north of the border, even if the profit margins aren’t as spectacular as cocaine trafficking to the United States is today. Salvadoran gangs proved that this is viable. (And no, Mexico will not be able to do what Bukele has, MS-13 was not short in psychopathy but El Salvador is a tiny country of 6 million and Bukele is an exceptional man. Perhaps the subject for a future article).

Government Measures Aren’t Working

Mexican authorities are quite hamstrung, unless they are willing to throw a massive amount of people in gulags for very long periods of time they won’t be able to eradicate these groups. And anything short of eradication in one fell swoop only brings great benefit and opportunity for the cartels that remain. It’s like a nasty disease that gains anti-biotic resistance after inadequate dosing. Right now, a corrupt soldier or police officer may be found to be corrupt and fired then serve a jail/prison term. What does he do with himself then? Right now his skills are in demand, paid for by the cartels. Perhaps he could join a private security group, though in their own way they also drive down the legitimacy of the government. Sometimes they turn criminal themselves. Indeed, one of the larger cartels, Los Viagras, started out as a citizens self-defence militia in 2014 to protect the people against the cartels.

Conclusion

To conclude, the organisational structure of the Mexican cartels has changed radically over the past few decades, particularly since 2006. Due to pressures of competition and the authorities’ High-Value Targeting, centralised familial mafias have largely been replaced by decentralised cartels, with the rising star, CJNG, employing system similar to McDonalds’ franchise system with outstanding results. Marijuana was long ago replaced in importance by the much more profitable cocaine, but neither may be necessary for the future survival of the cartels as they are entrenched. There has been a revolution in tactics and weaponry within the cartels. They have militarised and have successfully flexed their muscles against the state, extracting concessions such as the release of El Chapo’s son from custody. The implementation of technologies such as IEDs and/or FPV drones continues to make the battles more asymmetric and cartels more difficult to root out. The situation is especially difficult for the state because if it cracks down on one cartel it empowers the others. All cartels must be destroyed within a short time frame in order to ensure that they do not come back or that the survivors are empowered by the destruction of their competition. This is HARD. We shouldn’t see the cartels going away any time soon.

Support my work by donating to my Ko-Fi: https://ko-fi.com/bluevir

Addendum

Perhaps I will write future articles on what US intervention would look like, why Bukele’s actions were so effective and why its unlikely they’ll be successfully replicated in Mexico, the implications of America loosing control of its ability to restrict drugs and others. Leave suggestions in the comments, as always, discussion is heavily encouraged.

A few hours before the publishing of this essay, a holocaust style mass-cremation oven operated by CJNG was reported, presumably for their victims. 200 pairs of shoes were recovered.

Thanks for the article. This has been a growing topic of discussion lately. Regaining control of the Panama Canal and pressuring the Chinese government may slow the drug problem but as you mentioned, the cartels have diversified. Petroleum theft may end up more profitable than drugs anyways. I look forward to future articles on the subject!

Time for the 50-50-50 Plan. 3 steps:

1) Conquer 50 miles into Mexico to create a DMZ and deportation center.

2) Process and deport 50 million illegals going all the way back to the 1960’s.

3) Finish this in 50 months. One million deportations a month.

Conclusion: Hispanics walking the streets of America will be shot in the street.